What can I say: if this isn’t the ultimate celebration of North American cheese, I don’t know what is… I think every cheese maker and cheese lover should be able to experience this at least once.

What can I say: if this isn’t the ultimate celebration of North American cheese, I don’t know what is… I think every cheese maker and cheese lover should be able to experience this at least once.

City of Bridges

Maine Rocks! (Thanks Arlene!)

Saturday skips a breakfast meeting, and condenses the lunch break into the Brunch of Champions, so there were three different session blocks available.

First up: Cornerstone Project

Peter Dixon, Parish Hill Creamery

Rachel Fritz-Schaal, Parish Hill Creamery

Mark Gillman, Cato Corner Farm

Sue Miller, Birchrun Hill Farm

Moderator: Tom Bivens, Zephos scholar who focused on natural culture research

Earlier in the year you may have read about (or participated in) the Maine Cheese Guild’s trip to three cheese makers in Vermont at the end of February. And/or you may have read about (or attended) the Saturday session at the Denver ACS in 2017 where Peter and Rachel Fritz-Schaal described their experience working with natural cultures and then *touched on* the existence of the new Cornerstone Project. And/or you may have taken the workshop with Peter Dixon at Pineland Farms Creamery in 2015 that focused on creating and maintaining your own cultures.

And/or you may have found yourself in a bar in Lebannon, CT after the ACS Conference had concluded in 2015 sipping on a frosty pint of local brew when you overhear a conversation near you featuring a couple of cheese makers, one of whom wore a t-shirt and Carharts and a head full of red hair and a wild beard who was doing most of the talking about Albania and Macedonia and village cheeses being made with the evening milking that ripened overnight then the morning milking added in and it always resulted in cheese at the end, mostly good, sometimes fantastic, and sometimes challenging to get past the nose to the mouth. He then segued to talking about The Fabrication of Farmstead Goat Cheese by Jean-Claude Le Jaouen who says “remember this well: farmstead cheeses are always made from raw milk, they are the true product of the land.” The book describes the history of the cheesemaking process and the evolution of French goat cheeses which often depend on the local starter cultures because commercial cultures have only existed for the past 100 years or so. At which point he needs to deliniate the various traditional methods of creating starter cultures before mail-order:

The fellow with the beard tells the group about previous versions of natural culture cheeses that he’s made before: Livewater Toma at Westminster Creamery, and Manchester at Consider Bardwell, and he insists that a commercial cheese using only raw milk from a single herd, and only natural cultures found in that herd was possible: a true “taste of the milk and of the maker!”

Sitting at that table with Peter in that bar were Brian Civitello of Mystic Cheese in Lebannon, CT; and Sue Miller from Birchrun Hills Farm in PA. They all had been “called to action” by John Greeley at the ACS Competition Awards Ceremony that year to “create the next American Original” cheese. “It should be a taste of what we do on our land!” Sue added. “And the more we collaborate, the better our industry.” After talking about what it could look like they hatched a plan would soon become the “Cornerstone Project.”

Cornerstone Crowd: Tom Bivens, Rachel Fritz-Schaal, Sue Miller, Mark Gillman , and Peter Dixon

The group quickly asked one more cheesemaker to come aboard to collaborate on the development of this new cheese style: Mark Gillman of Cato Corner Farm, who at first didn’t understand why he was being included on this excited and active new email chain. And pretty quickly they settled on some ground rules:

And then Rachel takes full credit for working with Robert at Fromagex and deciding that the cheese should be made in a SQUARE mold, to extend the “Cornerstone” name and to represent “the first stone that anchors the building of this new American Original!” The four cheesemakers then bought every large square mold that Fromagex had in stock at the time. The very first trial make was at Birchrun Hill using their milk and Parrish Hill Farm natural cultures in 2015. The second trial make was in February 2016 at Parrish Hill with all four participants.

The group pictures this cheese style as a US hybrid of the PDO structure that adds some flexibility: variable aging, any type of milk (cow, goat, sheep, mixed, etc.), any type of wood boards as long as their local.

Rachel explained that it might take a few more years for all four cheese makers to ‘standardize’ the Cornerstone process and to agree on all of the necessary steps that new cheesemakers will need to take in order to be allowed to market their cheese under that name. It was also clear, hearing from Mark and Sue, that it is taking a while for these cheesemakers to figure out how to fit a natural culture into their production schedule, especially since they are not currently making a natural culture cheese every day. At the same time they both expressed excitement about the success they’ve had so far working with their own natural culture, and their hope to soon incorporate that natural culture into other styles of cheese that they make, both in the mesophilic and thermophilic families.

Finally each table was given samples of three different Cornerstone Cheeses to taste: one made in March of 2018 (Birchrun Hills), February (Cato Corner), and September of 2017 (Parrish Hill). The oldest cheese was the deepest in color, slightly drier, and much more complex (naturally, since it had aged 6 months more than either of the others), but they were all very good, each with it’s own subtle complexity and thermophilic acidic tang. Even with the oldest cheese the overriding flavor was “milky” as opposed to any single dominant flavor from a ripening agent (blue, or bloomy, or smear rind). In this way I can see how each of these cheeses clearly communicate the unique combination of their pastures, their herd, and the hand of the cheesemaker. Very exciting to think of 50 or 100 different Cornerstone cheeses in the future! However, this also made it difficult to picture a “Cornerstone” category in the ACS Compeition. Because who’s to say which terroir is the “Best?” Wouldn’t that defeat the idea that every cheese simply represents the farm and the maker?

MICROBIOME

Here an outline of how Peter Dixon develops his starter cultures:

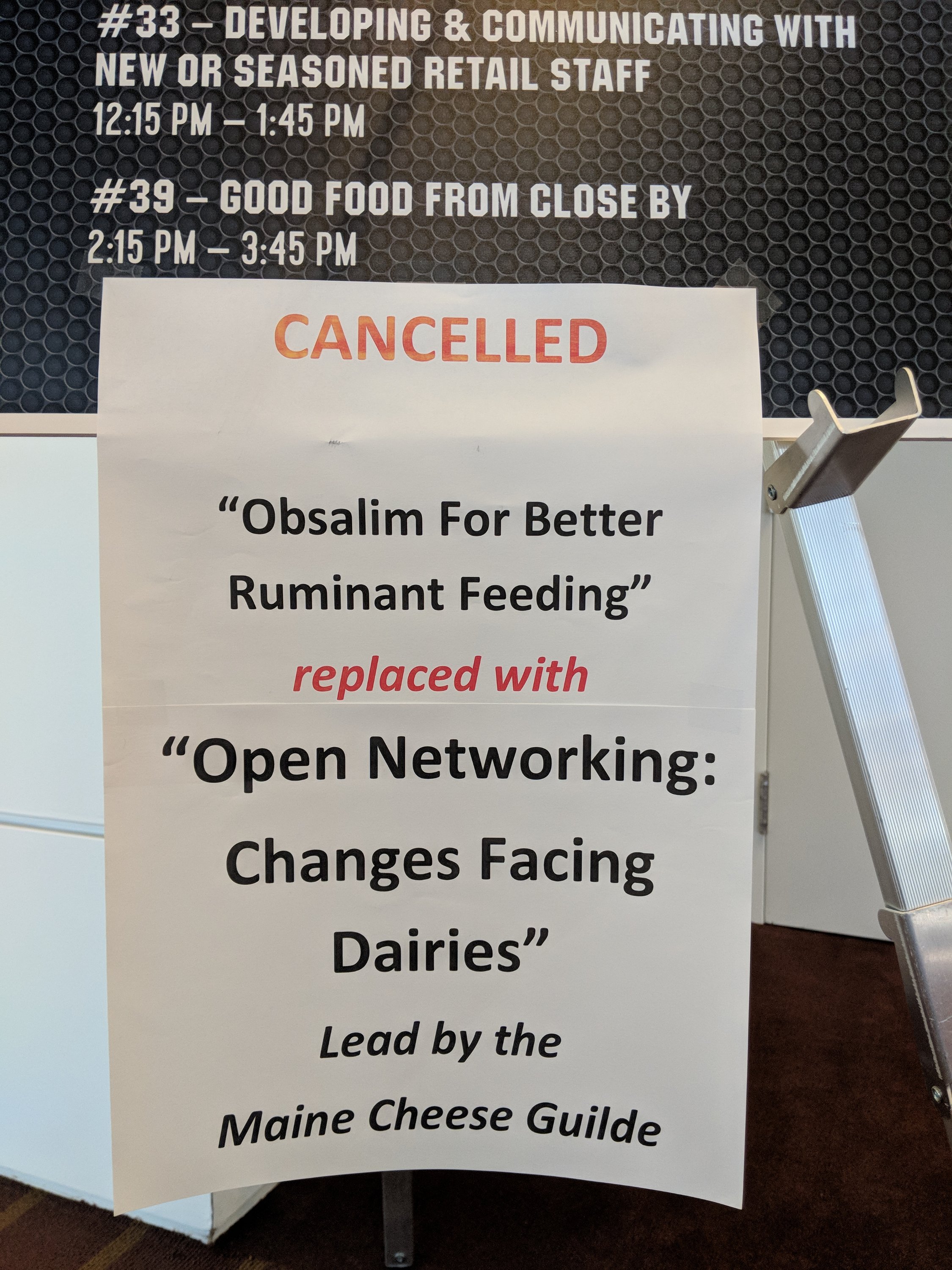

Recently a dairy science company called Eurofins offered to study Parrish Hill’s four grandmother cultures named after the cows from which they had come: Abigail, Clothilde, Helga, and Sonya. Here is what they found:

Microbiome of Parrish Hill Cornerstone starters

The analysis illustrates a typical thermophilic starter mix, which is appropriate because for Cornerstone Parrish Hill incubates their mothers at 105°F which favors only the thermophiles. You can also see that the balance of of species is different with each ‘grandmother’ which means that their cheese flavor (and probably acidification curve) would be different as well.

Building on this initial work by Eurofins, the University of Connecticut has offered to study all three farm’s natural cultures to find out what the geographic distinction of them actually is, as well as the mix of species.

After the Cornerstone Project presentation one of the questions from the audience had to do with the possibility of this Project inspiring a greater “democratization” of cheese making across the US and around the world. Sue pointed out that here in the US there are so few constraints on cheese makers to make specific styles of cheese, that the idea of using natural cultures was just another of the many “American Original” ideas that can catch on in the marketplace without a European precedent or analogy. Rachel was struck by the idea of the Project taking on a larger responsibility like “democratization” of the cheese world, though she did appreciate that using natural cultures could free some cheese makers from the expense of buying cultures. However, she also felt as though the “willingness to share” the knowledge gleaned from the development was another important component to the project, something that separated it from a typical commercial effort to develop a new cheese.

Then: The Breakfast of Champions

So Great! I got to taste the winner of the new “Boss of the Brunch” award, that is like Best in Show, but only for the breakfast type entries. This year’s winner was a ‘Herbed Rose Butter’ from Cherry Valley Dairy in Washington. It was super good, with a perfect salt balance, and the flavorings did not dominate, only help accentuate the buttery goodness.

Next up: Validation Challenges for the Makers of Unpasteurized Cheese

Bob Wills, Cedar Grove Cheese and Clock Shadow Creamery

Andy Hatch, Uplands Cheese Company

Kathleen Glass, Ph. D., University of WI-Madison

Jeremy Stephenson, Spring Brook Farms / Farms for City Kids

Bob, who is also the current chair of the ACE Foundation, felt that as we moved forward into the FSMA era of cheese making (the last deadline for compliance is this coming December), as well as beyond the idea that the 60 day rule can be considered a scientifically validated critical control point factor in making safe cheese, that cheese makers would benefit from getting additional information about how to best make raw milk cheeses.

He described the simplified flow of the cheese making process, and in the interest of time decided that they could focus only on the first two (of seven) steps: receipt of milk, and treatment of milk (before the culturing, setting and curd handling, draining, salting, and aging steps). What followed was a tutorial that focused on “alternatives to pasteurization” that could be proven to provide a “five log reduction in pathogens” the same way that pasteurization of milk is known to do.

Most of the session was turned over to Dr. Glass who initially introduced the “triangle of a Food Safety Plan that addressed pathogens: *Keep Them Out* *Keep Them From Growing* and *Kill All You Can* . She then began to dive into whether, at some point in the future, a scientific study would be able to generate a “matrix” of validated treatments that combined heat-treatment of raw milk (at lower than pasteurization temperatures), culturing, and aging, that would all combine into a specific log-reduction of pathogens. When/if such a matrix was generated (and it would need to be done by a ‘validated lab’ not simply by a cheese maker) it could give cheese makers many options for insuring that pathogen reduction was being addressed in the food safety plans. It would need to be a “matrix” of options because it depended on the possible pathogen levels found in the raw milk itself. The lower the initial levels, the lower the minimum log-reduction that would need to be applied for each recipe.

After Dr. Glass’s presentation Jeremy made a plea to the audience to continue the discussion about this topic after this conference session because “we need to communicate within our community.”

During the question section, a cheese maker justifiably asked why it seemed that Dr. Glass suggested that ALL raw milk for cheese making would need to be heat-treated to some extent? Bob replied that in the interest of the session time-frame he felt he could bring the group only one example of best practices for handling raw milk for cheese making, and this was what he chose.

Another person in the audience pointed out that with raw milk it seems like herd health is one of the most important factors. However, at the same time vet services are disappearing from more and more communities which means that it’s harder for dairy farmers to get the resources they need to maintain optimum herd health. Shouldn’t that issue be addressed in this context?

Another person offered that micro-filtration of milk might be a validated treatment of raw milk?(Micro-filtration is common in Europe where milk is pushed through a filter so fine that it removes all the microbiology, along with the cream. The cream alone is then pasteurized before being added back to the filtered milk.)

And finally: Conservation of Heritage Breeds in North America

Bronwen Percival: Neal’s Yard Dairy, UK

Jeannette Beranger: The Livestock Conservancy, NC

Sarah Bowley: SVP Foundation, RI

Dr. Mario Duchesne: Assoc. de mies en valeur des bovins de la race Canadienne dans Charlevoix

Moderator: Sam Frank, former Zephos scholar who focused on Heritage Breed research

This session is really a mash-up of the work that Sam has done on Heritage Dairy Breeds around the US and Europe, as well as the strident plea to increase the use of Heritage Breeds for cheesemaking made in the recent book by Bronwen and her husband Frances in Reinventing the Wheel.

Tasting the Farm System

Bronwen spoke first by providing an overview of what a heritage breed is and why it can be so important for the future of making complex cheeses that truly capture the Taste of Place. To whit:

Ultimately cheese is made up from the combination of the LAND, the ANIMALS on that land and what they eat, and then the MICROBES found around that land, in the milk, and that the cheesemaker chooses to add. “Cheese allows milk to express its inner character with much more fluency than when it’s consumed as a fresh liquid.”

This circles back to the breed of cow from which one sources the milk that is used to make cheese because when you have a Holstein in Maine it will need to be fed many of the same foods from the same processed sources as a Holstein in Pennsylvania or California. Where as if you had a herd of Welsh Black they could get much or all of its nutrition by grazing on the local plant matter, ideally those plants living on terrain on which it’s generally impossible to grow anything else. Though you probably get less milk from a Welsh Black than from a Holstein you will pay less to feed a Welsh Black (assuming you own sufficient grazing lands) and their milk will more closely reflect your Taste of Place.

However, as a cautionary tale as well as an introduction to the next three speakers, Bronwen’s last slide was a picture of a Sheeted Somerset cow, which had been the primary cattle breed used to make Cheddars in the 19th century until the Holsteins and Jerseys showed up and the breed became extinct. On top of the picture it read: “Genetic Variation is a key to adapting to different definitions of perfection.”

The Livestock Conservancy

(formally the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy)

So what can we do? Well, Jeannette Beranger from the Livestock Conservancy spoke about the work they do to actually conserve rare and endangered breeds of cattle, pigs, goats, sheep, donkeys, horses, rabbits, and poultry. Most of the work is to coordinate farmers who are committed to raising a few of at least one heritage breed, and help the larger community of different farmers focused on each breed coordinate sharing genetics, keeping lines clean but genetically diverse. Because for livestock breeds to “survive” then many different examples of that breed must live somewhere, and reproduce in a way that maintains the breed characteristics as well as its genetic strength.

Jeannette also made the point that although some breeds may be thriving, that in some way the genetics have changed so much over the last 100 years of “improvement” that one might even consider the “heritage Holstein” a different breed than the modern Holstein. (This same pronounced breed transformation has taken place in Jersey and Guernsey breeds as well.)

While the work of the Livestock Conservancy is to literally keep breeds *alive*, the SVF Foundation (whose grounds originally included the “Surprise Valley Farm” in Newport, RI) has taken another tack: to maintain a bank of genetic information on as many breeds as possible, so that if a breed suffers a population disaster or cannot be sustainably grown and maintained on farms, that there will still be enough saved (frozen in liquid nitrogen) germplasm (in the form of eggs, sperm, and oocytes) that the breed, and it’s genetics, could be resurrected in the future. Their goal is to maintain 200 embryos and 3,000 straws of semen for every breed.

The Story of One Endangered Breed: the Canadienne cattle

Dr. Mario Duchesne explained about the work that he and others do at the Association for the Development of Canadienne Cattle (Association de mise en valeur des bovins de race canadienne dans Charlevoix). Apparently this breed did not start out as such, but began as an amalgam of cattle imported from the Norman and Brittany coast in France, and thus included the first cows brought to the Charlevoix area of what would become Quebec. However since that 1609 settlement the bulk of these formerly French cows (likely including several of the French breeds at the time) were bred and adapted to the conditions in Canada that they coalesced into a recognizable breed that does not exist in France currently. They are particularly well suited to the harsh climates they faced in Canada and in 1850 there were close to 300,000 of them in Canada. However, in the late 1800s the “British Breeds” of Ayershire, Holstein, Jersey, and Brown Swiss arrived and displaced the Canadienne. In 1890 there were 100,000 Canadienne, by 1950s that had been cut in half, by the 1980s a tenth, and then by 2010 there were only 300 of them identified in all of Canada. However, with those 300 remaining cattle Dr. Duchesne pointed out that the remaining Canadienne herd still has more genetic diversity than all the Holsteins in Canada!

Dr. Duchesne’s team’s goal is to maintain and build a network of farms who are committed to the Canadienne breed and therefore resurrect the breed’s population, as well as rid it of unusual traits such as weak milk persistence during pregnancy. Currently those farms who are milking Canadiennes are allowed to use a new DOP label, ‘Le 1608″, when marketing products made from the breed.

At the end of the presentation there was a lively discussion sparked when one audience member asked the breed conservators: what is a “breed” exactly? That full discussion/debate will have to wait for another ACS Conference to fully be resolved.

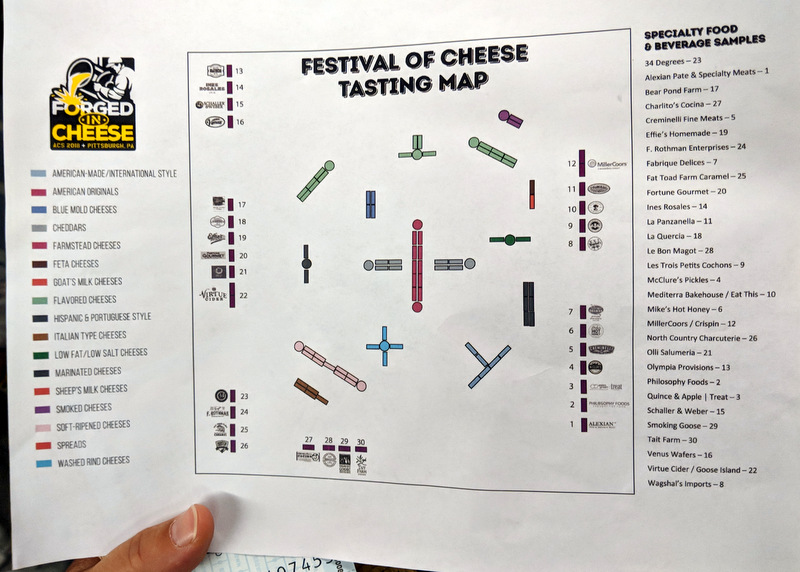

For me it was on to meet my aunt and uncle on “The Strip” for a frosty cold local beer. They had driven up from West Virginia and would later join me and Alison at the ultimate finale: The Festival of Cheese!

Our day began early, as it often does on Fridays, with a meeting of the Guild Leaders for breakfast. And right off there was a major success! Arlene had written to the ACS asking that there be some programming at the conference addressing the ongoing Dairy Crisis for both organic and conventional producers of fluid milk. At the meeting ACS Executive Director Nora Weiser announced that a previously scheduled presentation had to be canceled and that the ACS wanted to replace it with a networking forum on the issues around the Dairy Crisis. So important, and big thanks to Arlene for pushing that forward!

Nora updated the Guilds on the highlights of the topics that has been on the agenda to discuss with the FDA. Douglas Stearn from FDA would be updating the entire conference at lunch with a presentation, but she wanted to let us know:

Nora also announced that ACS was beginning the work on developing a Certified Cheese Maker exam, beginning with the established exam that Wisconsin currently uses.

It was great to see all our fellow Guilders, if only early on a Friday morning once a year. One other items brought up is that ACS helped to fund a website to promote communication and discussion among different Guilds year-round. Although it was launched last September there was still limited engagement with the website among more than one Guild (Maine!) but at the meeting the Guilders expressed a renewed interest in engaging in and using this tool.

And with that we had already gone 30 minutes over our scheduled time, but as Nora pointed out we almost always do, and she promised that next year she would build that in!

The Fight for Diversity in Food

Gordon Edgar, Rainbow Grocery Cooperative (Portland, OR)

Bronwen Percival, Neal’s Yard Dairy (UK)

Francis Percival, The World of Fine Wine

Simran Sethi, Journalist and Educator

A large crowd filled the meeting room where this panel discussion took place including some very big names in the cheese world to hear more details on what is clearly a very hot topic. And oh, my, what an exciting, important, and at times difficult conversation was had. This is the kind of session that really makes the trip to ACS worth the time and money.

If you don’t already recognize the Percivals names, they co-wrote the important new book on the history and future of a cheese industry focused on quality rather than quantity – Reinventing the Wheel. In that book they refer to an ideal kind of cheese as “Real Cheese.” That judgemental label would normally be controversial when speaking to a room full of cheese makers, mongers, and other industry professionals. It actually refers to a UK campaign to bring back “Real Ale” to British pubs. That campaign pushed back against the dominance of global common-denominator beers that had a stranglehold in British pubs for too long. Luckily in the US it didn’t take a public campaign to reverse the tide of flavorless industrial beer, it just took an increasing number of Craft Beer makers and consumers who sought out new and different beers (see Day 1 summary of the Fermentation Revolution for more detail!).

We’re all familiar with the “Artisanal Food” idea and claim, however they made the point that there is no true ‘certification’ of what “Artisanal” means. Therefore the term means whatever the person saying it wants it to mean, and therefore it is ripe for co-option by industrial food producers. It’s pretty clear that there’s a good chance small food producers will lose the ability to meaningfully use the term in the future. So when/if that happens where do we go?

Francis jumped right in to start the conversation by saying that he felt “Farmhouse” cheese better defined what he considered Real Cheese, and that Real Cheese was subversive at every level. By “Farmhouse” he indicated that Real Cheese is made with the cheese maker and the herdsman have a symbiotic relationship: the cheesemaker can tell the the herdsman how to change the way the barn is run, or visa versa. Simran asked what he meant by “subversive” because that’s not always a positive quality? He explained that at every step of the way the production of Real Cheese challenged the conventions of “conventional” farming practices, whether it was with the ideal forage, the best breed of dairy animal for each cheese type, and then the active encouragement of a *more* diverse microbial environment during the make process and into the aging cave, all the way through to the retail experience. “Let’s face it, cheese is an awkward thing to manage on a sales counter, as well as through all the steps it took to get there.” Another way he likes to define Real Cheese is as “the flavors of good farming.”

Bronwen added that she felt the cheesemaker’s role was to take the highest quality milk that they can find, execute a technically sound curd, and then step out of the way and let the quality of the milk that went into the cheese “shine through.” “What’s really exciting today is that the science is now able to test and validate the idea that better milk makes better cheese….Science is also debunking the conflation of milk quality with milk sterility. In fact cheese is perfect microcosm of the evolving thoughts on microbes and microbial communities.”

Simran expanded the idea of the challenges of creating Real Cheese from the milk quality itself to the labor aspect as well. Low wages have led to a lack of skilled dairy laborers which has moved many dairy farmers to look seriously at robot milking machines. Bronwen said that the important point of this story is not that the robots mis-handle the cows – on the contrary, they are well engineered to make the cows as comfortable as possible – but that the robot milkers are optimized for the production of liquid milk that is intended to be pasteurized (and chilled immediately). If the robot milker becomes more common that would reduce the opportunities for cheese makers to access milk in the specific way that they would like to receive it.

This was followed by an exchange among all the panelists about how hard it is to actually produce good quality milk for cheese making and that this work was often lost on the consumer. To counter this Bronwen pointed to Nick Millard the herdsman at Haford Cheese, the UK’s oldest organic dairy, who has become an Instagram star by illustrating the work that he does every day.

The problem, Francis said, was that of information asymmetry: we [the conference goers] know how much farmers work and what it costs to make good milk. The problem is that the customers do not know this, so all they see is the price of the resulting cheese. He pointed to the classic economics paper by George Akelof called The Market For Lemons, which focused on the used car market in the 1970s, and it proved that MORE information for the consumer increased the size of the market.

That said, Francis continued, it’s a very difficult ask of retailers to go into deep detail about why one specific cheese they sell is unique because the danger is that the parallel message the customer received is that all the other cheeses being offered are flawed in some way. Gordon said that this was true, but that a good retailer knew how to walk that line between featuring a cheese and denigrating others. He encouraged cheese mongers to “keep pushing the envelope with consumers” by walking them just a little farther down the education path each time you see them at the shop.

There is another danger, Simran pointed out: “We want to valorize but NOT fetishize the work!” Bronwen quipped: “Right, because it turns out pain tastes really really good!”

Gordon pointed out that the “Factory Farm” concept was developed in an attempt to counteract one of the Great Agrarian Myths: Self-Sufficiency. The first cheese factories were built as a way to relieve the “farmers wife” of the additional task of making cheese after the farmer had done all the work to milk the cows, not to mention grow the food to feed the cows. In many of the Agricultural reports in the late 1800s there is a regular plea to “free the farm wife of the burden of cheese making!” It was really successful model, but extended now 150 years that same model is now about to move to relieving the farm of the farmers…

At this point Francis and Bronwen wanted to make sure people understood that despite their illustrations of the benefits to Real Cheese of many of the old and “inefficient” methods of cheese making, that their counter mantra is to “Optimize without Compromise.” Francis told the story of a Loire goat cheese maker they visited that was making the most perfect old fashioned aged goat cheese logs that seemed to be the result of hundreds of years and many generations of perfecting the process. But when he asked the cheese maker about the years and generations of experience that went into their product, they laughed and said I used to be a bookkeeper and I wanted a change of pace, so I bought this business and the equipment four years ago then learned how to do it… Their advantage, Francis said, was that in the Loire there was a wealth of resources (refrigeration, equipment, herd management, etc.) devoted to chevre makers. That made it easy for a newcomer to achieve an optimized process quickly. It’s the cheese maker that has to “reinvent the wheel” at every step of the process, and has few options to access skilled resources who understand the business, and has to work with sub-optimal equipment who experience the “pain” we just talked about. However, THIS was where state and local governments could step in and invest in growing a specific industry (in this case cheese making and its ancillary businesses) without picking winners.

After all, a cheese maker can’t just do the work for love. The work has to be profitable and sustainable. She also said that in her historic research she found the prices of the new American factory cheese that was being exported for Britain where it could be sold for half the prices of Somerset Farmhouse cheddar in London. In today’s dollars, that “cut rate” cheese costs $75/lb. So although price pressure is a real factor in today’s marketplace, there’s something wrong when factory cheese is selling for 15x less…

From the cheese monger’s perspective, Gordon encouraged the retailers in the audience to commit to on expensive cheese for six months or a year in their shop, introducing as many of their regular customers to it as possible. “It won’t necessarily make you money, but it will do a good thing…and there are many stories about the difficult-to-sell cheese of today becoming the must-have cheese that is difficult to keep in stock tomorrow.

And with that Simran opened the floor to the audience.

One person asked Gordon or Bronwen if they knew of any mongers that organized their cases thematically in a way to identify a group of cheeses that had similar production philosophies. Neither of them offered an example, but Francis claimed that Bronwen was being too modest: at the Neals Yard Dairy shops the mongers often created a thematic structure to the display cases that weren’t always obvious to the buyer, giving those mongers an opportunity to dive a bit deeper into what cheeses they carried and why they were arranged that way. That said there are still no actual certification programs that can guarantee a product to be made exactly the way it’s described (in many cases).

When asked how the idea of diverse cheese being sold at its true cost squared up with the idea of the local cheese maker selling into local markets? Frances thought that instead of the primary focus being on the local supplier, that “good distribution makes good cheese” and that for a cheese maker to improve what they make they must, by necessity, “need to play against the Big Boys” in a global competition. However he was challenged by a dairy farmer who said that “the very people who care the most about diversity in cheese don’t actually care about competing world-wide.”

Another audience member asked how a focus on biodiversity in cheeses can square with the parallel focus on food safety? Bronwen pointed out that it is now very different in the industry than it had been even ten or twenty years ago, because “science is on our side!” Science is proving that cheeses made with a focus on biodiversity are being made safely. At the same time the fundamental question becomes what is the acceptable risk in eating any cheese, but particularly biodiverse cheese made from raw milk? If the answer is that no risk is acceptable then we’re lost. Because, as we see in the news all the time, NO food is without risk, including any kind of cheese. If we can quantify the risk of eating cheese, and then use science to reduce that risk to an agreed upon acceptable level, then we can have Safe Cheese that is Biodiverse.

Another audience member stood up to challenge the idea of “Farmhouse” cheese being the ONLY type of cheese that can be considered “Real Cheese” making the point that there are many cheeses made by cheese makers who do not produce their own milk, and yet have a limited or even single herd source for that milk, as well as a business relationship with that dairy farmer. Frances admitted that in France they do break up their classification system into “fermier” (Farmhouse), “artisanale” (small producer that buys in milk), “cooperative” (dairy with local milk supply that may come from multiple farms), and then “industriel.” He admitted that his idea of “Farmhouse” only is extreme, but on the other hand it’s the only label that’s externally verifiable. A small producer’s milk supply is only as good as the contract they’ve signed promising to purchase the milk, and those contracts can vary and are not always transparent to the consumer.

And then they had to end the discussion. Nothing was solved, but a lot was said about a subject that everyone clearly cares a lot about and continues to struggle with.

Afternoon session:

Large Farms can have Quality Milk, Healthy Animals, and Cow Comfort

Kim Bremmer, AG Inspirations

George Crave, Crave Brothers Farmstead Cheese

Brian Fiscalini, Fiscalini Cheese

Modarator: Kari Skibbie, Dairy Farmers of Wisconsin

This was an interesting session, but mostly because it was quite defensive in its attempt to equate two farms with herds of over 2000 cows each under management with the small 100 cow family dairy farm. Incredibly enough one of the farms is located in Modesto, CA where they boasted about being able to grow three feed crops each year, but during the Q&A had to admit that their water supply is not sustainable. According to this farmer they can stay in business only “if the water isn’t taken away from us.”