This year the Breakfast of Champions — when they present all the award winning cottage cheeses, ricottas, yogurts, and all other dairy products that were judged in competition but are awkward to eat during the Festival of Cheese — has become the Brunch of Champions AFTER the first round of sessions. Therefore I headed straight to…

SO YOU WANT TO BUILD A CHEESE CAVE?

hosted by Michael Kalish who held a workshop on affinage for the Guild back in March, along with David Mathieu from Clauger — who also made a presentation to the Guild at our May meeting — and a group from Air Quality Process.

The big challenge in most cheese caves is air flow management because the critical factors in aging — temperature and moisture — are both controlled through air flow. In some caves this air flow is passive, i.e. it is not mechanically aided. Because cold air sinks and warm air rises air can move through some caves using natural convection, and assuming that the stacked rows of cheeses do not interfere too much and that the target humidity can be passively controlled as well some cheese caves are a very simple system.

On the other hand, as many of us know, our aging areas need at least a little help in air flow management and this is where the equipment built and installed by both of these companies comes into play.

In this overview of the issues involved in building a working *and profitable* cheese aging facility they walked through all of the areas that need to be addressed:

- AIR

- EMPLOYEES

- FLUIDS

- PREMISES

- EQUIPMENT

- WORK PROCESS

- SUPPLIES

- AIR

Aside from their contribution to the aging and condition of cheeses all of these are either VECTORs or SOURCEs or both of potential contamination and that must be addressed as well. To complicate things further the cheese itself breathes water, oxygen, carbon dioxide, ammonia, as well as other gasses, and it also can generate significant heat during aging, especially when blue mold is involved.

While both companies have become experts in working with cheese makers all over the world (Clauger also builds air flow devices to aid in other food manufacturing settings such as salumi), their services do not come cheap. The entry price for their equipment is in the tens of thousands of dollars, and that assumes that a space has been built to perfectly accommodate their equipment. Often a re-design and/or a rebuilding of an aging facility is necessary in addition to the installation of their equipment. As they will point out, however, many cheese makers risk at least the same amount of money in their aging product at any one time and that a failure in air flow can cost manufactures dearly.

In addition to all of this advise on aging, I learned about a new word in the cheese process: RESSUYAGE. This translates into English directly as “soak” but it does not describe the washing of rinds as you might think. Many cheeses require a warm and moist period of aging (lasting from hours to about a day) after they’re removed from their molds but before the surface begins to dry off. It’s during this RESSUYAGE period that yeasts are allowed to become established which can often stabilize a rind as it heads into the cave, and then later spends time in a retail case. In France they often devote specific production rooms for this step, though if their product volume doesn’t justify a separate room a cheese maker will often park the cheeses to one side in their make room which is normally warm and moist anyway.

BRUNCH OF CHAMPIONS

What can be said for the opportunity to sample hundreds of delicious soft cheeses, yogurts, butters, “breakfast cheeses”, and the like for lunch? A picture is worth more than I could write here, so I’ll leave it at that.

CHEESE, SALAME, and MICROBES

Cheese has always been a means of preserving extra food that has been created today (milk during lactation) for leaner times tomorrow. (Anyone who is interested in the details of how cheese came to be through history should immediately find a copy of Cheese and Culture by Paul Kindstedt.)

Meat from larger animals presents a similar problem: slaughtering a pig or a cow (or even a sheep or a goat) presents many more pounds of meat than can be eaten, even by an entire family, at one sitting. And meat, like fresh milk, will spoil quickly without refrigeration, and even with refrigeration may only remain edible for a little over a week. We certainly recognize that in the past meat slaughter was often tied community-wide festivals to share with everyone. Each farm would contribute an animal occasionally, but they could then enjoy meat at each festival.

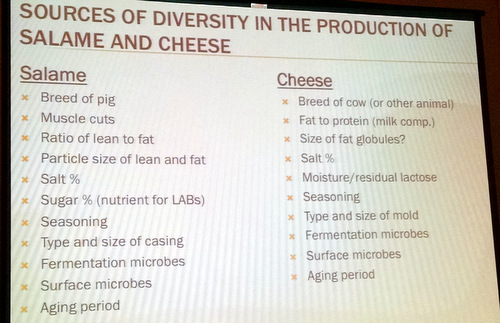

One healthy young hog fed through the growing season can present a family with almost 200 pounds of perishable food at slaughter time — what to do? Much like cheese you remove moisture, and add salt until the bacterial spoilage slows or stops. The parallels don’t end there, either, because it turns out that aging cheese and aging meat (primarily in the class of Salumi referred to as “Salame” which are dried and cured sausages and meats) share many bacteria and yeast and molds that are willing to digest muscle protein as readily as they will milk protein.

Once meats have been cut, chopped, or ground they are essentially the equivalent of cheese curds, and almost all of the resulting steps for fermentation and then aging (yes, there are some cheeses that are aged in animal skins!) are almost identical. Ultimately the goal is to use the bacteria and fungi to add enzymes to the protein structure in such a way that the proteins are broken into smaller molecules that “tenderize” the structure as well as create a desirable mix of flavors and aromas that we now associate with well made aged food.

The biggest microbiological difference between cured meats and cheeses is that scare iron in cheeses are the chief limiting factor in the growth of microbes, where as meat is an iron ocean to microbes. This may explain the much richer microbial diversity found in cheeses (no single microbe is strong enough to dominate) than in salame so far.

On the other hand the lack of sugars in meats means that the pH levels do not swing quite as widely as they do in cheeses — actually sugars (of any kind) are often an important ingredient in salame and it might not surprise a cheese maker to learn that adding more sugar makes a more acidic and sour flavored salame. (It might also not surprise a cheese maker that salame makers ALSO struggle to control the growth of Blue Mold — P. roqueforti and P. glaucus — !)

To pair with a tasting of six slightly different versions of the same salame (variations in starter culture and in sugar amounts) Mateo Keller of Jasper Hill Farm created slightly different versions of his Brie-stlye Moses Sleeper cheese, varying the inoculation of additional (adjunct) cultures, as well as creating one version out of an acid set, rather than rennet-set, curds. In addition he created an altered version of his 2013 ACS Best In Show winning Harbison.

Check out MicrobialFoods.org for more on this and other fascinating questions and discoveries about how much we depend on microbes to make the foods we love.

I ran into a Maine Cheese Guild friend from the past: Louella Hill. She apprenticed at “_blank”>Appleton Creamery, then went on to help found the Narragansett Creamery in Rhode Island. She now lives in California, is active in the California Cheese Guild, and was helping to run several of the conference sessions.

CHEESE and OLIVE OIL

Ever since I began attending ACS Conferences there have been cheese paired tasting sessions meant to evaluate combinations that work, and combinations that avoid. Some are traditional (cheese and wine, cheese and beer, cheese and cider) and some are unusual (cheese and coffee, cheese and chocolate). I chose this tasting because it is both traditional and unusual, and because it is tied closely to common California — and European — products.

Ever since I began attending ACS Conferences there have been cheese paired tasting sessions meant to evaluate combinations that work, and combinations that avoid. Some are traditional (cheese and wine, cheese and beer, cheese and cider) and some are unusual (cheese and coffee, cheese and chocolate). I chose this tasting because it is both traditional and unusual, and because it is tied closely to common California — and European — products.

Olives themselves are very common on a cheese board, but the whole olives served on any table are a fermented and cured product, just like cheese, so naturally they tend to pair well. Olive oil is pressed directly from the fruit and (normally) has nothing added to it. There are many traditional dishes made with Feta and fresh goats cheeses and olive oil. This session aimed to give us a broader idea of olive oil itself — differing in flavor and pairing from variety and blending as much as wines differ from each other — as well as to expand our ideas about pairings and possibilities.

Because the cheeses we would taste were familiar to us — a raw milk feta from Redwood Hill Farm, Sierra Nevada Cheese Co.’s chevre, an aged sheep milk cheese with peppercorns from Bellwether Cheese, and Crumbly Gorgonzola from BelGioso — the panelists spend most of their time teaching us about how olive oil is made and graded, the different varieties commonly used in oils from Europe and the US, as well as how to properly taste and evaluate different oils.

Sue Langstaff from UC Davis is a member of the California Olive Oil Taste Panel and has been a frequent judge at olive oil competitions. She walked us through the basics of olive oil chemistry, the standard tasting terms and how they correlate to various desirable characteristics or defects, and then the proper sequence for tasting: from a closed and warm container carefully open and sniff the accumulated aromas, then slurp in some oil to mix air through it, then “chew” the oil to make sure all of the aromas make their way up into the nasal receptors for a full appreciation. After that you can swallow or spit the sample, though Sue pointed out that “large quantities of olive oil can have a laxative effect…”

When we did our sampling and tasting, Sue also walked us through the creation of a simple five point spider graph measuring Overall Fruit, Ripe Fruit, Green Fruit, Bitterness, and Pungency. Regarding the last score, Sue helpfully pointed out that some of the more Pungent oils are either “one coughers, or two coughers.”

Along with the four cheeses we had four oils to evaluate: two blends and two single variety pressings, all from California. Once we had all charted our flavors, it was clear from the graphs that each of the oils were different, some very ripe fruity (peach, cantelope, chocolate, etc.), some green fruity (herbs, grass, pear, etc.), and others that drew more on the bitterness and pungency scale.

The first oil I sampled with the cheeses was a blend of Arbequina, Arbosana, and Koreneiki olives from Corto in Stockton, CA. It was super ripe fruit and “mellow” with little pepper bite or bitterness. It paired extremely well with the fresh cheeses, but not at all with the ripe aged cheeses which stomped all over it’s rich but soft flavors.

The second oil was a single varietal pressing of Ascolano from Lucero of Corning, CA. This oil had a lot of tropical and green fruit but also added a bit of pungency and bitterness making it the most balanced of the oils I tasted. It also paired well with the fresh cheeses, but not so well with the aged cheeses.

The third oil was a “Tuscan blend” of Frantolo, Leccino, Pendolino, Maurino, Lecchio del Corno, and Coratina from McEvoy Ranch in Petaluma. This oil had a LOT of fruit to it, plus a pungent kick on the back of the throat — at least a 1 cougher! It was good flavor, and very familiar to those of us who started tasting Extra Virgin olive oils from Italy. This oil paired nicely only with the rich flavored sheep milk cheese, however.

The fourth oil we tasted was a single varietal Koreneki olive oil. Koreneki is a small fruited but high yielding Greek olive variety known for its pungence, and this oil did not let us down. There was much less fruit than in the Tuscan blend, and plenty of coughing in the audience when we sampled it. Interestingly enough, however, this oil paired well with more cheeses than any other oil — everything but the Feta(!) worked with this oil.

THE FESTIVAL OF CHEESE

What can be said that hasn’t been said about this thing they call the Festival of Cheese? If you have not experienced an unlimited sampling of well over a thousand of the best of American artisan cheeses, then you should plan to attend AT LEAST the FoC next year in Providence. It is an awesome experience for anyone who likes cheese (and who doesn’t? ).

This year I focused on trying both cheeses from Best of Show award winner Farm For City Kids at Spring Brook Farm — they had a Tarantaise (BoS winner) and a Reserve Tarantaise (award winner). Having loved the samples of blue cheese at Point Rayes Farmstead Cheese Co. at the beginning of the week, so I got a bit of Bay Blue which won for best blue cheese this year, and also came in Third Place for Best of Show!

I’m also a big fan of Marieke Gouda cheeses that keep winning awards at ACS and beyond, especially her Marieke Foenegreek. I had to get two bits of that, plus one each of her other cheeses.

Add to that a few more interesting cheeses I spotted while making the rounds, a glass of Rogue Farms beer, and a few slippery slices of Fra’Mani meats and I was in heaven. Next year you could be too without having to fly 12 hours back and forth. See you in Providence!